Browse by Category

- All Categories

- 150th Anniversary

- Frederick County

- State Parks

- National Park Service

- Antietam

- Washington County

- Newcomer House

- 1865

- Literature

- Recreation

- Living History

- Museums

- Carroll County

- Historic Preservation

- Food/Dining

- Civil War Trails

- African American History

- Transportation

- Main Streets

- Education

- Women's History

- Geotrail

Bugle Call

Animating Antietam: a Q&A with Sean Moir

July 15, 2016

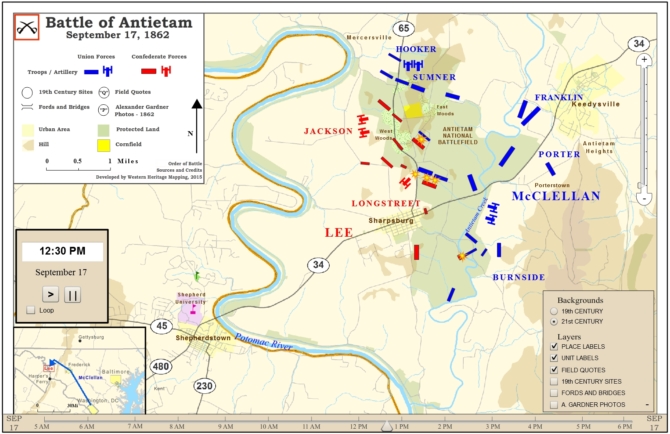

If you are a student of the Battle of Antietam, you've no doubt seen this animated map created by Western Heritage Mapping, demonstrating 13 hours of troop movements in 90 seconds. In this Q&A, map creator Sean Moir discusses the work that went into creating the map and points out features that make this digital history tool unique.

How do maps help people understand history?

Much of human history can be told in terms of who controls or administers territory. One could try to describe it in words, but it’s always much more enlightening to see territories and borders laid out graphically on a map. Maps are particularly useful when describing wars and battles. Traditional static maps are great for depicting or battle fronts and the placement of troops on the ground for a particular point in time. The advantage of animated maps is that they can show those fronts shift over time as well asdemonstrate how the troops moved and engaged over the course of the battle. Western Heritage Mapping has developed maps that show high level battle front changes, as in our World War I Theater map, as well as detailed troop movements which are shown in our Battle of Antietam animated map.

What tools did you use to create this animated map?

At Western Heritage Mapping our animated maps are developed using techniques that combine historic research, GIS data gathering and cartography, as well as Flash animation (ESRI’s ArcGIS suite of products and Adobe’s Flash Animation tool). Put together we have developed a methodology which is unique in the Digital Humanities universe.

Anything else viewers should know about this map?

Our animated maps have a number of features that may not be apparent at first glance. One important feature of this map is the ability to switch between a 21st century and a 19th century background. This transition is not as stark in Washington County as it is in other places. All of our maps give people the ability to roll the mouse over a particular unit to see its name. There is also a checkbox for showing 19th century sites, which in the case of Antietam includes the Heart of the Civil War’s Exhibit & Visitor Center at the Newcomer House. The Antietam map also has three unique features which we’ve not included on previous maps. The first is a selection of photographs from Alexander Gardner which were taken days after the battle. Most of the photos will be familiar to students of this battle, but geographic placement on the map is helpful for interpretation. Second, we show field quotes from generals at critical points in the battle. It is particularly interesting to see the Williams and Sumner quotes before and after Sedgwick’s assault around 9:00 AM. Finally, the divisions depicted in this battle are scaled proportionally to their troop strength. As the battle progresses the viewer can watch as divisions shrink, which becomes especially critical for the Confederate forces facing Burnside.

What other animated maps have you created? Any favorites?

Most of the maps we’ve created so far are related to the Philadelphia Campaign of 1777, where General Howe’s army marched from Elkton, Maryland to the colonial capital of Philadelphia. Among the battles we’ve mapped are the Battle of Brandywine, the Paoli Massacre, and the Battle of Germantown. Most of these maps were developed with grant money from the American Battlefield Protection Program (ABPP) and the National Park Service. In 2014, Western Heritage Mapping contracted with the Maryland Museum of Military History to create a suite of maps commemorating the 200th anniversary of the War of 1812. Two maps that stand out from this project are the Battle of Baltimore and the Battle of Bladensburg. Stevenson University in Towson was a partner in this project and even used our maps in the classroom as a demonstration of state-of-the-art public history.

How did you become interested in Civil War history?

In the 1990’s I lived in northern Virginia and was surrounded by Civil War sites like Manassas, Fredericksburg, and all the skirmish areas throughout the region. Since most of these are located in relatively rural areas, they are far better preserved than the Revolutionary battlefields near Philadelphia where I grew up. This gives the visitor a much better feel for the landscape and how it would have been viewed by Lee, Jackson, McClellan, and all the great 19th century generals. Living in Virginia also made me look at the war from a different perspective. The term “War of Northern Aggression” was never uttered in my school growing up, but I soon became accustomed to hearing it. Although today most Southerners would not wish for a different outcome to the war, it’s important for everyone to understand the complex motivations that drove the southern states into secession, and kept them battling for nearly half a decade.

What are some of your favorite places in the Heart of the Civil War, and why?

I have a personal connection with the Battle of South Mountain because I discovered it serendipitously while backpacking along the Appalachian Trail. It was amazing to see Civil War monuments high in the mountains along with the remains of Confederate trenches. It’s also interesting to drive through northern Frederick and Carroll Counties and think about the roads congested with Union forces organizing to head north to liberate south central Pennsylvania from Confederate troops in the days preceding Gettysburg. And it is hard to find a more peaceful and bucolic site anywhere on the east coast than Antietam.